Posted in 2015

Proof-Of-Work

The blocks in the block chain are created by nodes in the network, which called miners. A miner receives transactions from other nodes in the Bitcoin network. Every transaction is verified on arrival so that an attacker cannot maliciously transmit transactions to double spend a bitcoin. But the transactions are received in a non-deterministically which causes blocks to differ from miner to miner. Thus there needs to be a method to obtain consensus on the order of transactions among the nodes. Bitcoin uses a Proof-Of-Work (POW) system based on Hashcash.

As part of the POW system, a nonce is added to every block. The nonce is just a number but it is only accepted if the hash of the whole block begins with a certain number of zeros. Miners have to find the correct nonce for their block. The miner who finds the block receives a transaction fee as incentive to expend CPU time and electricity. It is possible that multiple miners find a valid nonce at approximately the same time and notify parts of the network of their newly found block. To solve this inconsistency, Bitcoin nodes save both branches and continue using the longest branch. At some point one branch will become predominant in the network as more nodes will dedicate computing power to extend this branch and the smaller branch is then abandoned.

The average time taken to find a block in a bitcoin network should be 10 minutes. Every two weeks, the number of zeros needed in the beginning of the hash of the transaction is adjusted to compensate for the fluctuating speed of the network to find a block. The difficulty of finding a block is directly proportional to the number of zeros.

One of the alternatives to POW is Proof-of-Stake. The video below explains it in comparison to POW.

Block chain

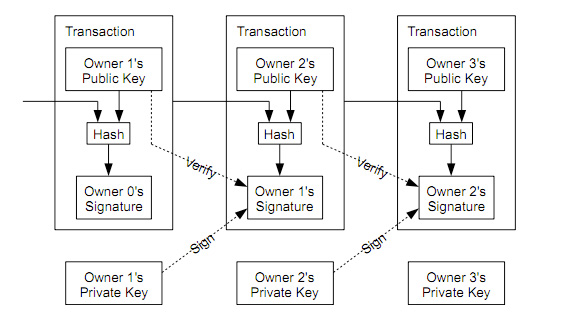

Block chain is the main technological innovation of Bitcoin. It was introduced by Satoshi Nakamoto as a timestamp server as part of the Bitcoin protocol. A block chain is a public ledger shared by all nodes participating in a system based on the Bitcoin protocol, that is, all nodes in the network have a copy of the entire block chain. A full copy of a block chain contains every transaction ever executed. Thus it is a proof of all the transactions on the network. But what is a transaction? A transaction is a transfer of Bitcoin value which is broadcast to the network and collected into blocks. A transaction typically references previous transaction by concatenating it with the public key of the new owner and hashing it. The current owner digitally signs this hash and sends it along with the public key of the new owner. A payee can verify the signatures to verify the chain of ownership.

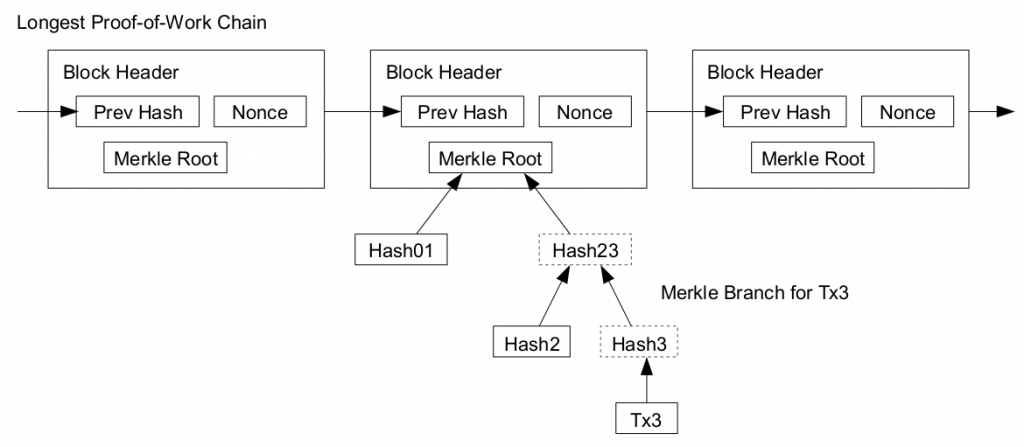

Every block in the block chain contains a hash of the previous block such that a chain of blocks is created from the first block of the chain, also known as genesis block, to the current block. This way the blocks are arranged in chronological order. Due to the Proof-Of-Work, it is also computationally infeasible to modify a block as every block that follows must also be regenerated. These properties prevent double-spending in bitcoins. Double spending had been a threat to digital currencies before bitcoin. This is because unlike physical money, digital currency can be easily duplicated.

Considering all nodes in the network have a copy of the block chain, if every transaction is added to the block chain, then the size of the block chain will will sooner or later become to large. Instead just the merkle root of the merkle tree formed by the transactions to find a block can be used. To compute the merkle root, copies of each transaction is hashed, and the hashes are then paired and hashed, paired again and hashed again until a single hash remains, the merkle root of a merkle tree. The merkle root is stored in the block header. Transaction verification can be performed using Merkle Hash trees without checking the transaction itself.

Currency to Cryptocurrency

Bitcoin is a cryptocurrency, a digital currency which uses cryptography to create money and secure transactions. The transactions are processed in a decentralized manner such that the users do not need to trust any single party. The transactions are recorded in a blockchain which is a public ledger and can be cryptographically verified by anyone. This is a fascinating concept and one can find many resources to read about it, starting with Satoshi Nakamoto’s paper.

But before understanding bitcoins, there is one question that needs to be asked. What is money? And where does is come from? In the book Atlas Shrugged, Ayn Rand wrote,

Have you ever asked what is the root of money? Money is a tool of exchange, which can’t exist unless there are goods produced and men able to produce them. Money is the material shape of the principle that men who wish to deal with one another must deal by trade and give value for value. Money is not the tool of the moochers, who claim your product by tears, or of the looters, who take it from you by force. Money is made possible only by the men who produce.

It is a common notion that money is a commodity. But is it? Money can take multiple forms. Money can can take the form of commodity, paper or merely a value. The video below explains the transition from gold standard to fiat currency to bitcoin.

Below is a video [from 1:35 till 2:50] where a person with no prior experience with money finds it hard to grasp why the image in only a particular form (bank note) is of value and not otherwise. [I think the scene conveys the message even if one does not understand the dialogues]

https://youtu.be/x5Qb2b6nQFc?t=95

Finally a video on what gives money its value.

Zimmerman Telegram

On the interception of the Zimmerman telegram, the German diplomatic code 0075 was noticed by the British. Kahn mentions in (Kahn, 1967), Room 40 knew from its analyses that 0075 was one of a series of two-part codes that the German Foreign Office designated by two zeros and two digits, the two digits always showing an arithmetical difference of 2. Among the others, some of which Room 40 had solved, were 0097, 0086, which was used for German missions in South America, 0064, used between Berlin and Madrid and perhaps elsewhere, 0053, and 0042.” Initially only part of the long message was deciphered. But Zimmerman’s signature could be read. Code 0075 was a two-part code of 10,000 words and phrases numbered 0 to 9999 in mixed order. This was a gigantic monoalphabetic substitution cipher where instead of 26 alphabets, thousands of codes with low frequency were involved and whose characteristics were less defined than English alphabets. When a Code is intercepted, the initial identifications are first marked by pencil and placed in “pencil groups”. When confirmed by further traffic, they are placed in “ink groups”. But Room 40 did not have enough Code 0075 messages to decipher the Zimmerman telegram in total. Zimmerman telegram was partially deciphered but enough to obtain the core of the message. Though US entry into the war would have helped the Allies, there were enough arguments against informing the US. First, Room 40 was one of Britain’s darkest secrets. If a partially deciphered message is sent to the US, it would expose “Room 40”. Second, this would expose Britain’s habit of supervising telegrams of neutrals Third, this would lead to Germany using new codes instead of 26 alphabets, thousands of codes with low frequency were involved and whose characteristics were less defined than English alphabets.

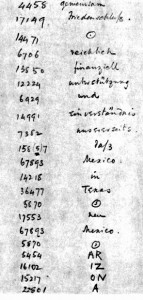

The chief of Room 40, W.R. Hall, then devised a plan to obtain the telegram from Mexico. He thought that the German mission in Mexico may not have Code 0075 and might use an older code. He obtained a copy of the Zimmerman telegram as received in Mexico and realised that Code 13040, which was an older code, was used to encipher. This code was easier to decipher as Room 40 had intercepted many transmissions using the same code. A portion of the decrypted code is shown below. It can be observed that the word Arizona is not in the German codebook and has been split into phonetic syllables.

Hall showed the message to the secretary of the US embassy after few days. The secretary of the US embassy in Britain then sent the message to the US President. He himself did not know of the existence of Room 40 but wanted to keep his involvement secret. The authenticity of the telegram was initially doubted by the US government. But all doubts were eliminated by Zimmerman himself when he admitted to having sent the telegram (Boghardt, 2003). The telegram was published in newspapers and the citizens of US, who were initially against the war, pushed the government to participate in the war. The US involvement reinforced the Allied troops. “Room 40” was merged with British Intelligence unit MI1b to form Government Code and Cypher School which was later renamed as Government Communications Headquarters (GCQC).

References:

Kahn, David (1967), The Code Breakers: The Story of Secret Writing, Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Boghardt, Thomas (2003), The Zimmermann Telegram: Diplomacy, Intelligence and The American Entry into World War I (PDF). Working Paper Series. Washington DC: The BMW Center for German and European Studies Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service, Georgetown University. 6-04.

Room 40

In August 1914, British cable ship Telconia entered the North Sea and the men on-board cut the transatlantic cables and hence cut-off Germany from communicating through wired lines to the rest of the Western Europe and USA (Kahn, 1967). This forced Germany to use radio for all communication or use cables controlled by the Allies and hence allowed the Allies to intercept. In contrast, the British and French used wireless to communicate with ships at sea and not otherwise.

But Britain had no formal codebreaking organization even though intercepts were piling up. The Director of Naval Education, Alfred Ewing, put together a team of mostly volunteers from naval colleges to work on the intercepts. But they made no real progress. It was in September 1914 that the German cruiser Megdeburg was wrecked in Baltic and the Russians were able to obtain two cipher and signalling books from a drowning German officer. The Russians gave one of the books to the British. But Ewing’s team could not find any correlation between the four letter words in the books and the intercepts. Later it was found that the code had been superenciphered by monoalphabetic substitution. With the codebook in possession, deciphering became easy. Some codewords appeared more frequently, allowing for frequency analysis. Also the consonants appeared alternately with the vowels in the German codewords. The British acquired two more codebooks, one from a German-Australian steamer, Hobart, and another from the sinking German destroyer SMS S119 in the battle of Texel Island. With increasing number of intercepts and more men being recruited to decipher them, Ewing’s team moved to a large room Room 40, which lead to the organization informally being called Room 40.

Most intercepted messages reported the whereabouts of Allied ships. Though interesting, this information was not vital to the British. They recognized that the Germans also used short wave which the British could not intercept with the available infrastructure. So a station was set up to monitor shortwave signals and information about the movements of the High seas fleet was obtained. Even though it was no secret that the British had access to the codebook, the German’s continued to use the same until mid-1916. The book was massive and it could not be easily changed. But they did increase the frequency of changing the keys for monoalphabetic substitution. At the beginning of the war, the key was changed once in 3 months. In 1916, it was changed every midnight. But Room 40 had developed expertise and only needed few hours to find the new key every day.

Room 40 played an important role throughout the war. Winston Churchill wrote, “Without the cryptographers’ department there would have been no Battle of Jutland”. But the most important contribution of Room 40 was to decipher the Zimmerman telegram in 1917 which lead to America’s entry in the war. In this telegram, the German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmerman offered Mexico the territories of Texas and Arizona if they join the war as a German ally. The message was sent from the US embassy in Berlin through Copenhagen and London to the German embassy in Washington. It was to be retransmitted to Mexico from there. The message read as follows:

We intend to begin on the first of February unrestricted submarine warfare. We shall endeavor in spite of this to keep the United States of America neutral. In the event of this not succeeding, we make Mexico a proposal of alliance on the following basis:Make war together, make peace together, generous financial support and an understanding on our part that Mexico is to reconquer the lost territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. The settlement in detail is left to you. You will inform the President [of Mexico] of the above most secretly as soon as the outbreak of war with the United States of America is certain and add the suggestion that he should, on his own initiative, invite Japan to immediate adherence and at the same time mediate between Japan and ourselves. Please call the President’s attention to the fact that the ruthless employment of our submarines now offers the prospect of compelling England in a few months to make peace.

Zimmerman

Reference:

Kahn, David (1967), The Code Breakers: The Story of Secret Writing, Weidenfeld and Nicolson

Implication of ‘Human Chipping’ on personal identity – Part 2: Are we artificial by nature?

Most human beings will consider implantation of RFID chips in the body as unnatural. But what is natural? One could say that what we are when we are born and the genetic information that we pass on to our children is natural. We are born naked, but we wear clothes to keep ourselves warm. Clothes are not natural to us. We are deprived of properties such as think skin or fur which many other animals have (Gehlen, 2003). We fulfill our requirements using technology.

It is natural that people contract diseases such as cancer and AIDS. Earthquakes and hurricanes are natural disasters. But these are not necessarily good for human beings. If it is possible to improve the situation through technological intervention, then why not? Like all changes in the society be it technological or not, the benefits are countered by the negatives. If the benefits outweigh the negatives then transhumanists would claim that there is no necessity for being skeptical about the technology (Bostrom, 2007).

Aristotle said that nature is grown while technology is made. Habermas claims that these categories de-differentiate when we interfere with nature (Habermas, 2003). He says humans should act morally as self-creating and autonomous beings. He claims that intervention leads to one category of ‘programmers’ and another of ‘programmed’. The ‘programmer treats the other person as object and has an attitude of domination while the ‘programmed’ will feel less free and lose autonomy as the attitude and behavior will be encoded. If Habermas’ categorization is applied to ‘Human Chipping’, the person or the organization who are implanting RFID chips on other human beings are the ‘programmers’ while the person with the implant is the ‘programmed’.

Let us consider the situation where newly born children are implanted with RFID chips. Initially these chips are used for identifying the infant in the hospital. This chip would be useful to monitor the health of the child throughout its life. Here there is no possibility of informed consent though. So the ‘programmed’ has no autonomy on choosing if it wants to be programmed or not. Humans are ‘by nature’ artificial and have no ‘natural origin’ and thus humans are a prosthetic being. Human evolution is the result of technical exteriorization of life. Humans are not autonomous but are ‘programmed’ by technology (Stiegler, 1998).

References:

Bostrom, N. (2007). In Defense of Posthuman Dignity. Bioethics, 206-214.

Gehlen, A. (2003). A Philosophical Anthropological perspective on technology. In R. C. Dusek, Philosophy of Technology: The Technological Condition: An Anthology (pp. 213-220). Blackwell Publishers.

Habermas, J. (2003). The Future of Human Nature. Polity Press.

Stiegler, B. (1998). Technics and Time: The fault of Epimetheus. Stanford University Press.

Implication of ‘Human Chipping’ on personal identity – Part 1: Are we Cyborgs?

The first RFID implant on a human being was performed in August of 1998 on the upper left arm of Professor Kevin Warwick in Reading, England (Gasson, ICT Implants, 2008). The implant was cylindrical in structure having a length of 22mm and diameter of 4mm. The doctor required to make a small hole, place the RFID chip and close the incision with couple of stitches. The implant allowed Professor Warwick to control lights, open doors and even receive welcome messages when he arrived. His location in the building could be tracked and monitored. This was only experimental and hence other possible applications of the technology were not considered by the scientists at that time.

One of the first commercial application of RFID chips was to replace ‘medic alert’ bracelets by VeriChip Corporation in 2004 (Gasson, ICT Implants, 2008). It was approved by the FDA in the United States of America for human use. It was used to relay medical details when linked to online medical database. For example, the details of the patient’s diabetes can be stored in the chips and because it is implanted, the patient cannot forget it or lose it. Later on the company also used these chips for infant protection and patient monitoring in hospitals. Subsequently these chips were used by nightclubs in Barcelona and Rotterdam to allow access to their VIP members. For example, at the Baja Beach Club in Rotterdam, these chips were implanted in their VIP members and were used for not only entry into the club but also for ordering drinks. For instance, if a member bought a drink, the chip could be read by an RFID reader and the amount can be deducted from the bank directly without the member getting hands on his/her wallet.

In these applications of ‘Human Chipping’, it can be seen that these RFID chips become a permanent part of the person. A person who has an RFID Chip in his arm for some time would become used to its functionality and would not think of it as an electronic component but instead as a part of his body (Gasson, Human implants from invasive to pervasive at TEDxGoodenoughCollege, 2012). How is the RFID implant any different from a person’s leg, hand or any other part of the body? If a person loses their legs in an accident, he will not be able to walk. If prosthetic legs are used he would be able to walk again. These prosthetic legs are made to function as legs such that the person is not able to differentiate it from his legs. They become a part of the person and not as an external component that he has worn. Similarly for the person whose diabetes is being monitored by the RFID implant, the chip becomes a part of the body. If the chip is removed, then the person’s existence would become difficult. His body will not function properly. If we are considering the chip as part of the body, aren’t we cyborgs?

One experiment done by researchers from Vrije University in Amsterdam amplifies the argument that we have become cyborgs. Their experiment involved placing a malicious computer code on a RFID tag, so that if the tag is read by the building system it would get infected by the virus (Rieback, Crispo, & Tanenbaum, 2006). Depending on the virus, it could disrupt the functioning of the building system or spread the virus to the tags used by others. Though this experiment sheds light on the security issues of the technology, we can look at its implications on personal identity. The spread of the computer virus using the implant is analogous to the spread of a communicable disease such as tuberculosis. The virus originates from the RFID tag implanted in a person and passes on to others. It is not possible to separate the RFID tag from the person and say that the virus originated from the tag but not from the person. Think of a situation in which this computer virus corrupts the functioning of every RFID chip that it infects. It might be fatal to a person whose insulin intake is dependent on the RFID chip. This could be a criminal offence but only if the chip is considered as part of the offender, which would make the offender a cyborg.

References:

Gasson, M. (2008). ICT Implants. The Future of Identity in the Information Society, 262, pp. 287-295. Retrieved from BBC: http://www.19.bbc.co.uk

Gasson, M. (2012). Human implants from invasive to pervasive at TEDxGoodenoughCollege. Retrieved from TedX: http://tedxtalks.ted.com/video/Human-implants-from-invasive-to

Rieback, M., Crispo, B., & Tanenbaum, A. (2006). Is your cat infected with a computer virus? IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communication, (pp. 169-179).

Technological implants- Therapy or Enhancement?

Technological implants in human beings is not a new phenomenon. The pacemaker is used by many people around the world to help their heart function appropriately. For the past few years, cochlear implants have been performed on people whose hair cells in the inner ear become unresponsive. In this case the implant acts as a replacement for the lost functionality of hair cells. In both these examples, technology is used as a therapy in order to assist in normal functioning of the human being. In the case of cochlear implants, it has been observed that the person with the implant takes few weeks or months to get used to it. It is claimed that though the person is able to hear sounds again, the sounds that they hear is different from what they had experienced before going deaf. In the case of a child which is born deaf, the sounds heard due to the cochlear implant will be the only sounds known. Technology here is a mediator in helping humans achieve their goal of being able to hear sounds. There is no original perception mediated by technology but the mediated perception itself is the original (Ihde, 1990). But what if cochlear implants allowed humans to hear ultrasonic sounds. Humans without cochlear implants cannot hear ultrasonic sounds. In this case, would cochlear implants be a form of therapy or enhancement?

One of the first commercial application of RFID implants was in the field of medicine in order to monitor the patient. This would be considered as a therapy by the hospital. But if we consider the umpteen number of people who do not have access to such technology but have the same diseases, it does seem that patients with implant are privileged and that the implant is an enhancement to their functioning as human beings. Some might say that the privileged ones are ‘better than normal’ (Kurzweil, 2005). They can upload their information or data into the database of the hospital through the internet unconsciously. They don’t need to click a button to send the information. In certain regards, they are uploading a part of themselves which could be looked upon as extending their memory (Clark & Chalmers, 1998). They may not consciously know or remember their current blood sugar level but the medical database of their hospital is updated with the information that can be accessed later if needed.

One possible application of RFID chips would be to implant them on finger tips of a person. Let us consider that a policeman is implanted with an RFID chip containing an infrared sensor, which senses heat, on the index finger of his right hand. If he is entering a house which is dark to catch a crime suspect, he can find in which direction the suspect is by just spatially moving his hand. This gives him additional power compared to his colleagues and is certainly an enhancement to his ‘human qualities’. But Professor Mark Gasson from Reading University has a different view. He does not consider the implants as an enhancement (Gasson, Human implants from invasive to pervasive at TEDxGoodenoughCollege, 2012). Though very few people have RFID implants now, he thinks that soon almost everyone will have it. He compares RFID implants to mobile phones. Earlier very few used mobile phones but in a few years almost everyone in developed and developing nations considers it as a necessity and feels out of place if they do not have a mobile phone. It is possible that in the near future, implants may not remain optional but may become compulsory.

References:

Clark, A., & Chalmers, D. J. (1998). The Extended Mind. The Philosopher’s Annual, XXI, 10-23.

Gasson, M. (2012). Human implants from invasive to pervasive at TEDxGoodenoughCollege. Retrieved from TedX: http://tedxtalks.ted.com/video/Human-implants-from-invasive-to

Ihde, D. (1990). Technology and the lifeworld. Indiana University Press.

Kurzweil, R. (2005). The singularity is near: When humans transcend biology. Viking/Penguin Group

The technology used when you borrow books from the library

In my last blog post I briefly described RFID technology. In this blog post I will give one implementation example as seen in the TU Delft library.

The books in the library have a paper thin passive RFID tag attached to the backcover. This tag contains information related to the book, mostly in the form of a unique identification number. When you want to borrow a book, you can use one of the self checkin/checkout stations. You need to place the campus card (if student or employee of TU Delft) or library membership card on the card reader to identify yourself. On placing one or several books on the self checkin station, the RFID tag is read by the reader. Placing multiple books on top of each other should be avoided as the reader may not be able to identify individual books due to tag collision. The reader communicates with a server to inform that one or several books have been checked-in by the identified visitor and this information is stored in the database. When you return (checkout) the books to the library, a similar sequence of events take place. If you require assistance, the librarian at the service desk can help you by using the checkin/checkout station available at the service desk. While leaving the library, you pass through exit sensors (another reader with a longer detection range than checkin/checkout stations) which verifies if the book has been checked-in. If the book has not been checked-in, an alarm is triggered.

Normally you will be exposed to RFID technology in the above mentioned form. Sometimes, the RFID tag attached to the book may not have the right information or a new book may have arrived. In such a scenario a conversion station behind the service desk is used by the librarian to write the required information on a new tag and attach it to the book. RFID technology also makes it easier for the librarians to search for individual books requested from the depot and for inventory checks.

RFID

At the TU Delft, one can observe the widespread usage of Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) technology. The campus cards have a RFID tag in them, the doors of the rooms in the university have a RFID reader which is used for access control, while in the library RFID systems are used in multiple ways such as self-checkin and checkout stations, exit sensors, etc. Traveling by public transport in the Netherlands requires OV-Chipkaart which has a RFID tag.

The basic elements of RFID have been known since the Second World War. Airplanes had an identification signal which enabled the ground stations to distinguish their own aircrafts to those sent by the enemy. RFID technology works on the principle of radio frequency transmission-reception. Most RFID systems use the unlicensed spectrum. Low Frequency (125-134.2 KHz) and High Frequency (13.56MHz) bands are used in cheaper systems and these are used for example in animal tagging. Ultra High Frequency bands and ISM bands are used in smart cards and item management (as in the library).

An RFID system is made up of two components – a tag (or transponder) and a reader. A tag, which represents the actual data carrying device of an RFID system, normally consists of a an antenna and an electronic microchip that contains a radio receiver, a radio modulator for sending response back to the reader, control logic, some amount of memory and a power system. There are two types of tags – passive and active. An active transponder possesses its own voltage supply (or battery) while a passive transponder does not. An active tag has a larger reading range and is less commonly used due to its costs and shorter shelf life. A passive tag is only activated when it is within the response range of a reader. The power required to activate the tag is supplied through the contactless coupling unit as is the timing pulse and data. There are also semi-passive tags which have a battery but use the reader’s power to transmit a message back. It must be noted that some tags are programmed by the manufacturer and are ‘read-only’ while others are reprogrammable.

A reader are continually on and typically send a radio signal and listen for a tag’s response. Depending on the RFID system, the reader communicates by Amplitude modulation (AM), Phase modulation (PM) or Frequency modulation (FM). The tag detects the energy and communicated with the reader by varying how much it loads its antenna. By switching the load rapidly, the tag establishes its own carrier frequency and sends back the tag’s serial number and some other information as well. Most tags transmit only a number which the reader sends to a computer. If the tag is used for access control, then the computer will check if the number is in the list of numbers that is allowed access. If it is present, then the computer might energize the solenoid to unlock the door.

References:

1. Lahiri, S. ( 2006). RFID Source Book. IBM Press.

2. https://www.rfidjournal.com/