Zimmerman Telegram

On the interception of the Zimmerman telegram, the German diplomatic code 0075 was noticed by the British. Kahn mentions in (Kahn, 1967), Room 40 knew from its analyses that 0075 was one of a series of two-part codes that the German Foreign Office designated by two zeros and two digits, the two digits always showing an arithmetical difference of 2. Among the others, some of which Room 40 had solved, were 0097, 0086, which was used for German missions in South America, 0064, used between Berlin and Madrid and perhaps elsewhere, 0053, and 0042.” Initially only part of the long message was deciphered. But Zimmerman’s signature could be read. Code 0075 was a two-part code of 10,000 words and phrases numbered 0 to 9999 in mixed order. This was a gigantic monoalphabetic substitution cipher where instead of 26 alphabets, thousands of codes with low frequency were involved and whose characteristics were less defined than English alphabets. When a Code is intercepted, the initial identifications are first marked by pencil and placed in “pencil groups”. When confirmed by further traffic, they are placed in “ink groups”. But Room 40 did not have enough Code 0075 messages to decipher the Zimmerman telegram in total. Zimmerman telegram was partially deciphered but enough to obtain the core of the message. Though US entry into the war would have helped the Allies, there were enough arguments against informing the US. First, Room 40 was one of Britain’s darkest secrets. If a partially deciphered message is sent to the US, it would expose “Room 40”. Second, this would expose Britain’s habit of supervising telegrams of neutrals Third, this would lead to Germany using new codes instead of 26 alphabets, thousands of codes with low frequency were involved and whose characteristics were less defined than English alphabets.

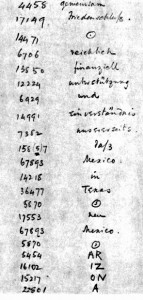

The chief of Room 40, W.R. Hall, then devised a plan to obtain the telegram from Mexico. He thought that the German mission in Mexico may not have Code 0075 and might use an older code. He obtained a copy of the Zimmerman telegram as received in Mexico and realised that Code 13040, which was an older code, was used to encipher. This code was easier to decipher as Room 40 had intercepted many transmissions using the same code. A portion of the decrypted code is shown below. It can be observed that the word Arizona is not in the German codebook and has been split into phonetic syllables.

Hall showed the message to the secretary of the US embassy after few days. The secretary of the US embassy in Britain then sent the message to the US President. He himself did not know of the existence of Room 40 but wanted to keep his involvement secret. The authenticity of the telegram was initially doubted by the US government. But all doubts were eliminated by Zimmerman himself when he admitted to having sent the telegram (Boghardt, 2003). The telegram was published in newspapers and the citizens of US, who were initially against the war, pushed the government to participate in the war. The US involvement reinforced the Allied troops. “Room 40” was merged with British Intelligence unit MI1b to form Government Code and Cypher School which was later renamed as Government Communications Headquarters (GCQC).

References:

Kahn, David (1967), The Code Breakers: The Story of Secret Writing, Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Boghardt, Thomas (2003), The Zimmermann Telegram: Diplomacy, Intelligence and The American Entry into World War I (PDF). Working Paper Series. Washington DC: The BMW Center for German and European Studies Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service, Georgetown University. 6-04.

Comments are closed.